Abstract

The use of extreme dynamics and modes of attack emphasizing the percussive qualities of the piano, as well as abrupt changes in intensity and registers characterize much of the piano music written in the second half of the 20th century (Caillet, 2007). It is not rare to find, in this repertoire, dynamics ranging from pppp to ffff, and even a sustained use of extreme violence which manifests itself in the repetition of notes, chords, clusters or other forms of writing emphasizing fortissimo nuances.

However, from the point of view of the pianist’s physical well-being, we know that a repetitive muscular effort can generate potentially serious injuries, and that the promotion of a “quality movement” may, on the contrary, promote a “free, expressive and secure” performance (Mark, 2003, p. 5).

Several works on piano technique offer solutions to most of the problems posed by the performance of standard piano repertoire, which spanned from the second half of the 18th century through the first decades of the 20th century (Chiantore, 2019, pp. 700-702), being based mainly on repertoires which are out of phase with our chronological time.

Thus, taking major consensual issues of piano technique as a starting point, and relying equally on my own practical experience as a performer devoted to the piano music of our time, I propose an itinerary through different works calling upon extreme dynamic nuances, from which I will draw a repertoire of movements that have allowed me to manage these repertoires without injury in course of a career spanning over more than two decades.

The use of extreme dynamics and modes of attack emphasizing the percussive qualities of the piano, as well as abrupt changes in intensity and registers characterize much of the piano music written in the second half of the 20th century. It is not rare to find, in this repertoire, dynamics ranging from ppppp to fffff [1], and even a sustained use of extreme violence which manifests itself in the repetition of notes, chords, clusters or other forms of writing emphasizing fortissimo nuances.These aspects integrate a general tendency for recent composers to develop the full sonorous and technical potential of the piano, at the same time enlarging its acoustic space and privileging sudden ruptures in the musical discourse, as opposed to the classic phrase scheme “arsis/accent/thesis” (Caillet, 2007, p. 55)[2]. Catherine Vickers (2008, p. 2) attributes to Karlheinz Stockhausen the statement ‘Dynamics in music are totally weak and underdeveloped’, and affirms that: “As early as 1967, he called for a ‘tonometer’ with a light column with which performers could control their dynamics.”

To this aesthetic shift corresponds a “peak of power” in piano construction, which, according to Kreidy (2012, p. 65), would happen in the first decade of the 21st century, although “the instrument’s main organological characteristics [were] consolidated” from the beginning of the previous century (Chiantore, 2019, p. 702). Simultaneously, according to Martingo (2018, p. 146),

Martingo goes on to state that “[…] musical performance historically presents a continuous extension of the body apparatus, whose domain of fine motor skills implies a corporal discipline, repetition, and deferred bonus that configure a rationalized practice with a high level of self-control.” (Martingo, 2018, p. 148)[4]

It may be rather surprising to note that, while an expansion of corporal media associated with piano repertoires and practices was unfolding throughout the 20th century, theorization about body mouvements, or piano techniques, decreased since 1929, the publication date of Otto Rudolf Ortmann’s The Physiological Mechanics of Piano Technique (1929). On the other hand, most works on piano technique offer solutions to the problems posed by the performance of standard piano repertoire, which spanned from the second half of the 18th century through the first decades of the 20th century (Chiantore, 2019, pp. 700-702), being based mainly on repertoires which are out of phase with our own chronological time.

Yet, the proliferation of books and treatises on piano technique in the beginning of the 20th century, some of which I will briefly refer to in my following comments[5], can be seen as a natural response to the revolution operated by the piano music of Franz Liszt. According to Chiantore (2019, p. 345),

Liszt’s piano technique reveals a hitherto unknown variety in touch. We are still a long way from the systematising of Tobias Matthay or Rudolf Maria Breithaupt, because Liszt’s focus was, from the beginning, figurations, rather than the actual process of converting them into sound.

Those figurations included octaves (simple and broken), tremolos (in simple and double notes, including trills and repeated notes), double notes, simple notes. Their physical realization relied on a set number of “fundamental mechanisms”, such as arm rotation or weight (Chiantore, 2019, p. 346). Once again in Chiantore’s words,

It is impossible to say whether Liszt perceived this conceptual distinction between written formulas and muscular resources with the same clarity we find in some 20th-century treatises, but there is no doubt that his own production was the first to allow and foment proposals of this kind. (Chiantore, 2019, pp. 346-347)

When Liszt’s disciple William Mason set himself to elaborate on the nature of his master’s piano technique, in his four-volume Touch and Technic, or the Technic of Artistic Piano Playing by means of a New Combination of Exercice-Forms and Method of Practice, op. 44 (Mason, 1892)[6], he considered three basic kinds of motions: Finger touches, Hand touches and Arm touches. (Chiantore, 2019, p. 348)

Arm touches are particularly important, since they combine the two fundamental elements, weight and muscular impulses, which have since been considered “the two forces that rule pianistic actions – gravity and the kinetic energy produced by the muscular apparatus” (Chiantore, 2019, p. 352). Furthermore, Liszt was fully aware of the “swing”, or upward arm motion resulting from the previous striking of the keys, which Adolph Kullak named Ausschwung (Kullak, 1855).

In combining these essential upward and downward arm gestures in a myriad of infinite possibilities, the piano technique derived from Liszt allowed for performers to “organically […] handle […] devilish passages” (Chiantore, 2019, p. 352), while simultaneously fostering the development of timbrical modulations hitherto unconceivable.

In a seminal work published in 1995, On piano playing: motion, sound and expression, Gyorgy Sandor relates the same fundamental principles to dynamics, stating that volume production in piano playing depends solely on the “speed with which the hammer hits the string” (Sandor, 1995, p. 6). Furthermore, he affirms:

In order to mobilize the playing apparatus and generate the desired speed in the hammers, there are no other but two sources of energy available: the force of gravity […] and muscular energy. […] These forces, and their combinations, provide all the sources of energy available to activate the entire playing equipment. […] It will be up to us to determine when to utilize the force of gravity exclusively, when to use muscular energy exclusively, and when and how to combine both. (Sandor, 1995, p. 7)

After warning against the futility of putting extra pressure on the keys after having struck them, Sandor goes on to conclude:

Weight alone is also of little use, unless it is set in motion. […] Muscular force is of use only in generating speed in the hammers, not as energy spent statically. The simultaneous and extended activation of an antagonistic set of muscles […] is unproductive, and in spite of a vigorous feeling of energy and tension in the arm, it is totally superfluous and therefore should be avoided. All it causes is immobility and stiffness, which ultimately result in a poor sound. The inescapable conclusion is that technique must concern itself with setting the hammers in motion, using the force of gravity, and expending a minimal and efficient amount of our own muscular energy. A maximum fortissimo as well as the lightest pianissimo can be produced by these procedures in a completely effortless manner. (Sandor, 1995, p. 8)

Sandor furthermore warns about the limitations of volume production on the instrument, stating that

[…] the piano, like any other musical instrument, is limited in the amount of sound it can produce and in the responsiveness of its mechanism. […] Under no circumstances must one exert oneself when playing fortissimo! Although the piano can produce a tremendous volume, its maximum sonorities will come about not when the maximum amount of energy is used, but when the limits of elasticity in its mechanism are arrived at but not surpassed. (Sandor, 1995, pp. 14-15)

Lev Oborin, in turn, highlights two key aspects: for one thing, he states that the “successful development of technique” depends first and foremost on “psychological and physical freedom” (Oborin, 2008, p. 70). He defines the latter as follows: “The sense of freedom I am talking about means that only the essential muscles are involved in my work, and the whole of piano playing is in fact based on the rapid successive tensing and relaxing of muscles” (Oborin, 2008, p. 71). On the other hand, he stresses the importance of the involvement of the whole arm, hand and finger apparatus in playing. According to him, “Sound is obtained from the piano in various ways, by various movements, depending on the character of the music, but basically it should be created by using the entire arm, properly coordinated.” (Oborin, 2008, p. 73)

The idea that loud volume may be obtained through the engagement of the whole upper torso is verbalized by Grigorii Prokofiev, Soviet pianist who studied with Konstantin Igumnov at the Moscow Conservatoire: “In a large forte the initial fundamental energy even comes from the torso – all the remaining links of arm and hand are merely transmitters of energy. Here all the links of the hand, upper arm, shoulder, and torso are called into play” (Igumnov, 2008, p. 81). In line with that though, Joseph Lhevinne stated: “Of course strength, real physical strength, is required to play many of the great masterpieces demanding a powerful tone; but there is a way of administering this strength to the piano so that the player economizes his force” (Lhevinne, 1972, p. 29). He then introduces two distinctive elements: posture and the role of the wrists as “shock absorbers”. Commenting on a sketch of Anton Rubinstein playing the piano, Lhevinne points out: “[…] instead of sitting bold upright, […], he is inclined decidedly toward the keyboard. In all his forte passages he employed the weight of his body and shoulders” (Lhevinne, 1972, p. 29). And he goes on to notice that, if there is no “banging” noise in Rubinstein’s loud passages, that is due to the fact that his “wrists were always free from stiffness in such passages and he took advantage of the natural shock absorber at the wrist which we all possess” (Lhevinne, 1972, p. 31). His conclusion stresses the importance of the quality of sound in playing loud dynamics: “There is an acoustical principle involved in striking the keys. If the blow is a sudden, hard, brutal one, the vibrations of the wires seem to be far less pervading than when the hammers are operated so that the wires are “rung” as a bell.” (Lhevinne, 1972, p. 32)

To summarize, we should note that, since the time of Franz Liszt, emphasis has been put on the connectedness of finger, hand and arm movements, with the latter assuming a prominent role through infinite combinations of micro-movements relying either on the force of gravity or on muscular impulses, which in turn generate upward and downward movements. The resulting freedom of movement, in a broader sense, has been proclaimed by pianists, professors and theorists, associated particularly, but not exclusively, to the so-called Russian school of piano playing, such as Lev Oborin, Grigorii Prokofiev, Joseph Lhevinne, Arthur Rubinstein and others; in these cases, the realization of extremely loud dynamics has been thought to be more effective when the whole torso is mobilized; quality of sound, even under those extreme circumstances, was thought to be indispensable and ought to be assured by the pianist, who should avoid a “blowing” type of playing in favor of an approach comparable to “ringing bells”. In much the same way, supported by a thorough explanation of pertaining anatomical questions, Gyorgy Sandor emphasized that fff dynamics depend solely on the speed of hammer descent, which in turn is conditioned by the pianist’s arm “weight” and muscular impulses; he equally warned that the instrument itself bears physical limitations in what extreme dynamics are concerned.

From the point of view of the pianist’s physical well-being, we know that a repetitive muscular effort can generate potentially serious injuries, and that the promotion of a “high-quality movement” may, on the contrary, promote a “free, expressive, and secure” performance (Mark, 2003, p. 5). That high-quality movement, which is attainable though designing, rehearsing and performing a specific choreography for each piece of music, relying on smaller partial movements, corresponds largely to the notion of playing “freedom” to which I alluded earlier on.

According to Thomas Mark (2003, pp. 6-7),

Every piece of music consists of a series of notes different from any other piece of music […], so every piece requires its own series of movements. It is appropriate to insist, as some teachers do, that the movement should be as complex as the music.

Complex, varied movement is indeed what we see in free players. But it is not usually what we see in injured pianists. […] Stereotyped movement makes piano playing more repetitive than it needs to be and is an important cause of injury.

On the other hand, Mark (2003, p. 130) warns that “Many pianists use excessive force, which is a cause of injury. […] It can also contribute to a harsh, inexpressive tone.” In that sense, the author echoes Sandor’s and Lhévinne’s remarks, through an anatomically and physiological perspective.

Indeed, there seems to be a very strong correspondence between the recent scientifically informed perspectives of Mark (2003), Sandor (1995) and Fink (1992), and the practice-based precepts of earlier pianists, piano professors and theorists. Yet, as I have said before, most of them address exclusively, or are based upon repertoires ranging from the 18th to the early 20th centuries, leaving out of their scope a whole range of piano music written since 1950 and into the 21st century which, as already mentionned, can be extremely demanding in what forceful dynamics and modes of attack are concerned. At the same time, we should note that most books dealing with contemporary piano performance issues do not specifically or deeply address the matter of extreme dynamics. Catherine Vickers (2008, pp. 3-11), for instance, suggests a number of exercices for developing dynamic differentiation, but gives no advice concerning how to obtain such dynamic effects, incluind extreme ones. Alan Shockley (Shockley, 2018), in turn, lists an incredible number of contemporary piano techniques and resources, but again does not address the specificities of body movements involved in making those techniques and resources actually sound. A number of academic thesis and dissertations (e. g. Vaes, 2009; Proulx, 2009; Ishii, 2005; Hudicek, 2002) provide interesting and extensive insight on extended piano techniques, but leave mostly out of their discourse the questions that I intend to bring forth in this study.

How can a pianist deal with those exigencies while maintaining a healthy and sustainable approach to piano performance? Is the advice compiled in the lines above useful for a 21st century pianist having to perform extenuating works by Pierre Boulez, György Ligeti, Karlheinz Stockhausen, Iannis Xenakis[7] and so many other composers? If so, are there any adaptations required, that may actualize piano technique as inherited from the Lisztian tradition, specifically in what concerns extremely loud dynamics?

Taking the previously evoked major consensual issues of piano technique as a starting point and relying on my own practical experience as a performer devoted to the piano music of our time, I propose an itinerary through different works calling upon extreme dynamic nuances, from which I will draw a repertoire of movements that have allowed me to manage my pianistic activity without injury during a career spanning over more than two decades.

Let us start with the use of the force of gravity. Gyorgy Sandor (1995, pp. 41-51) gives detailed instructions on what he calls “free-fall” and suggests specific exercises to develop that technique. He states: “There is no question that the piano’s biggest sonorities can be achieved by the free-fall motion.” (Sandor, 1995, p. 46) Free-fall supposes three phases: lifting the structures involved (fingers, hand, forearm or whole arm), letting them fall according to the force of gravity, and landing. Because free-fall depends on time and distance for the acceleration process to take place, it is reserved to “passages in moderate tempo” (Sandor, 1995, p. 45).

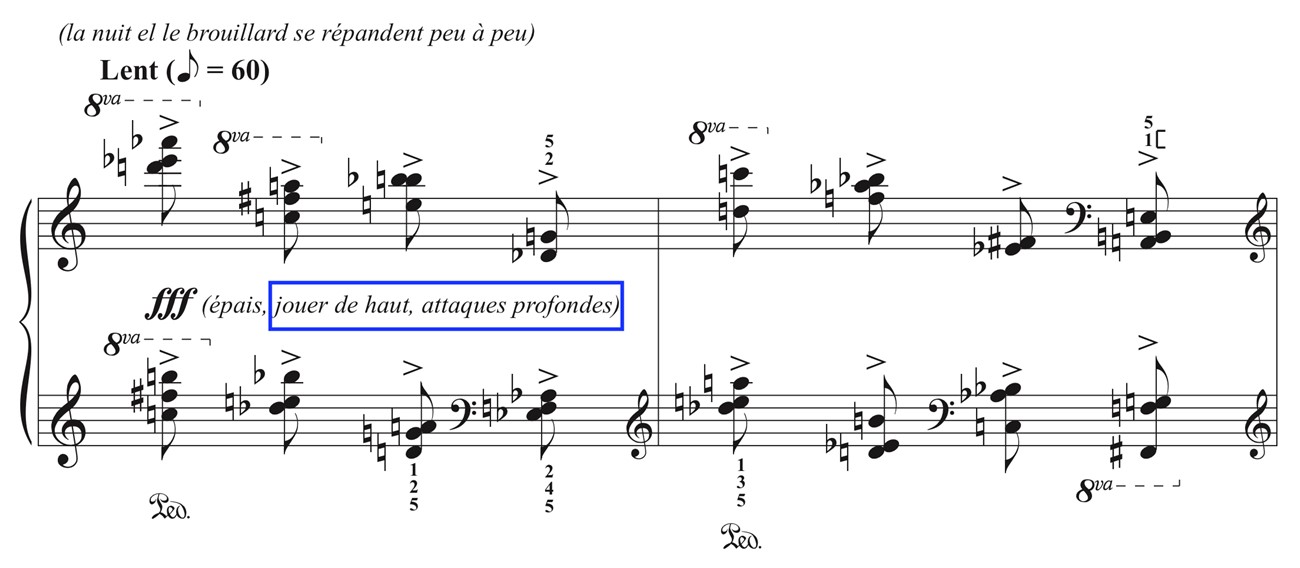

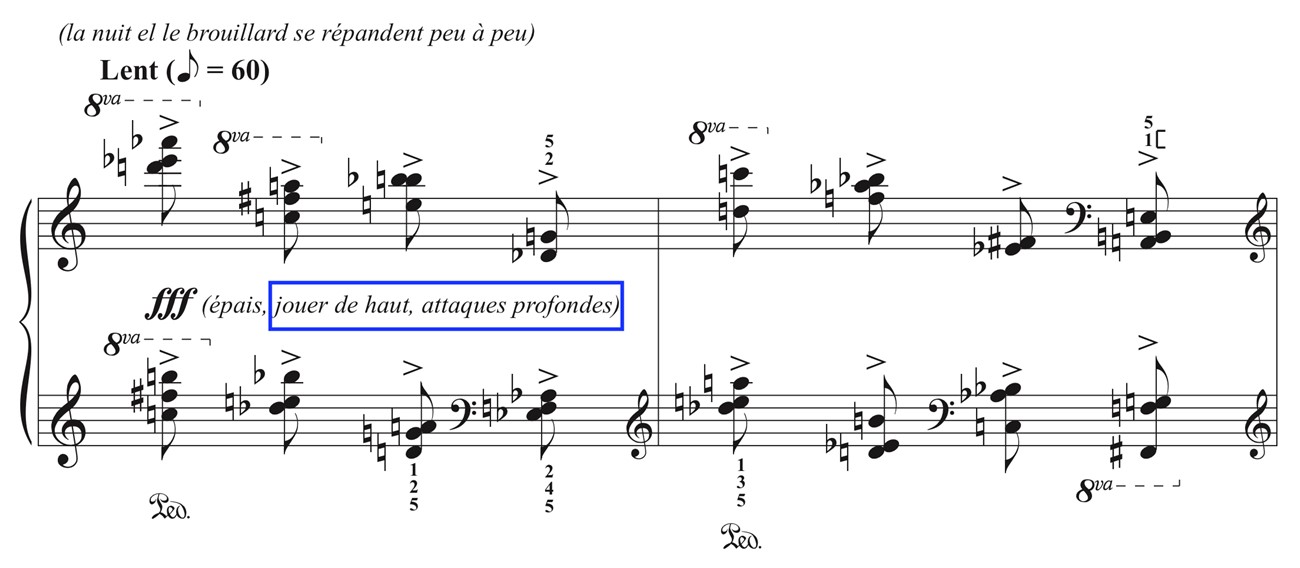

I have used the whole arm apparatus in free-fall while aiming to achieve a potent fff in Olivier Messiaen’s Le Courlis Cendré (from Catalogue d’Oiseaux, Vol. 7). Indeed, on page 16, the composer calls for that nuance, which he defines as “thick”, directing the pianist to “play from above”, with “deep attacks”.

Figure 1. Olivier Messiaen, Le Courlis Cendré (from Catalogue d’Oiseaux, Vol. 7), p. 16

Note: Transcribed from the Alphonse Leduc Edition[8]

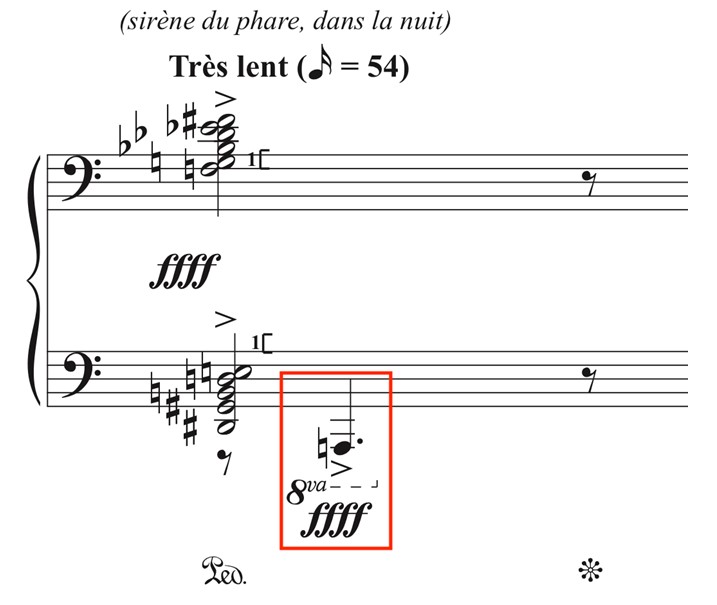

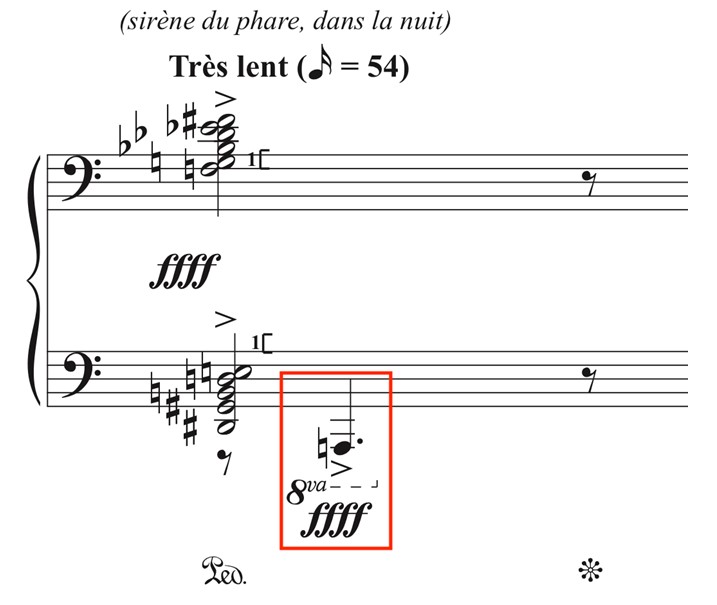

Later, in the same piece, Messiaen calls for a ffff nuance in a motif that portrays a lighthouse’s siren at night, in sharp contrast with the surrounding sounds of nature that the piece evokes. In order to expand free-fall’s distance and apply the whole torso in playing the single lowest note of the piano in that motif, I chose to play it not with the left hand, as would be expected, but with the right hand; I used the third finger because of its central alignment with the hand and arm, slightly curved and falling in a totally vertical manner, as suggested by Sandor (1995, p. 46).

Figure 2. Olivier Messiaen, Le Courlis Cendré (from Catalogue d’Oiseaux, Vol. 7), p. 17

Note: Transcribed from the Alphonse Leduc Edition

Notice that both passages I used to exemplify strict free-fall movements unfold at a slow tempo, which allows for the application of that technique. Yet, in passages calling for different notes to be played, in which there is a risk of hitting the wrong keys, the free-fall technique must be replaced by the “thrust” approach, which, according to Sandor (1995, p. 108)

[…] is executed purely by active muscles, and neither the force of gravity nor weight are employed. Instead of raising the arm, hand, and fingers and exposing them to the gradual acceleration of the force of gravity, we place the fingers right on the surface of the keys and push the keys down with a sudden instantaneous contraction of some of the strongest body and arm muscles […]

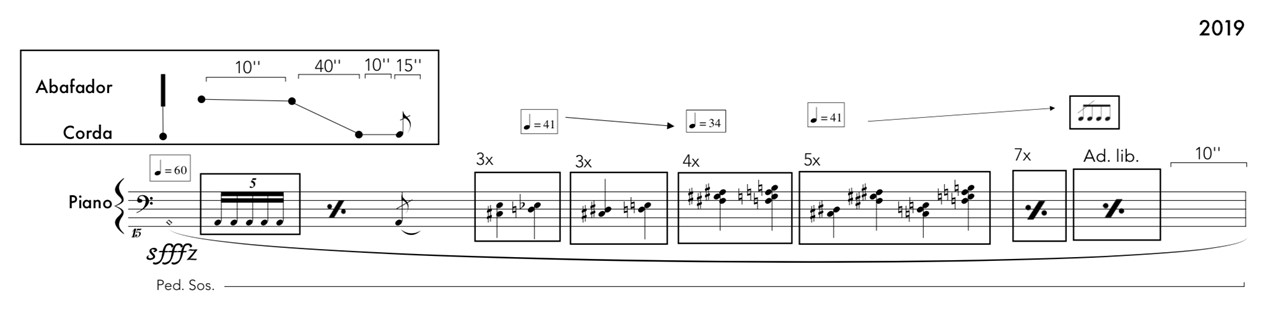

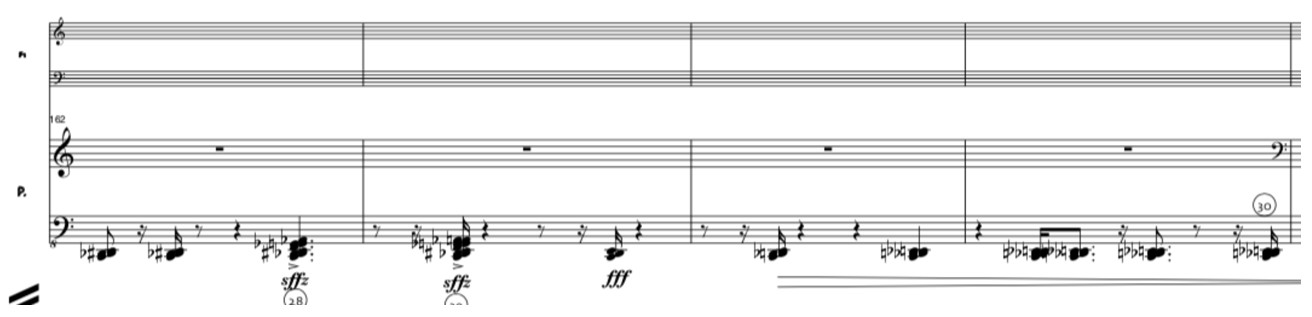

I have used that approach in my performance of Carlos Marecos’ A casa do cravo (2019), for piano and electronics, where even though the tempo is moderate, some note changes are sufficiently rapid to bear a potential risk of failure if free-fall is applied. Of course, the use of such “sudden instantaneous” muscle contraction needs a corresponding release of tension, which is why I have followed each attack by a great rebound, in the form of a bold upward movement of the whole arm (cf. Figure 3).

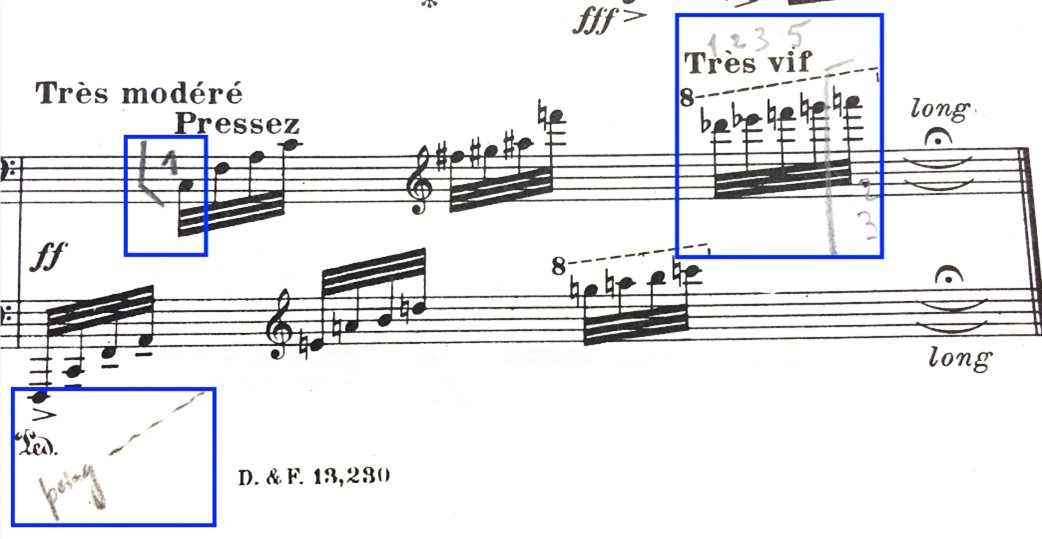

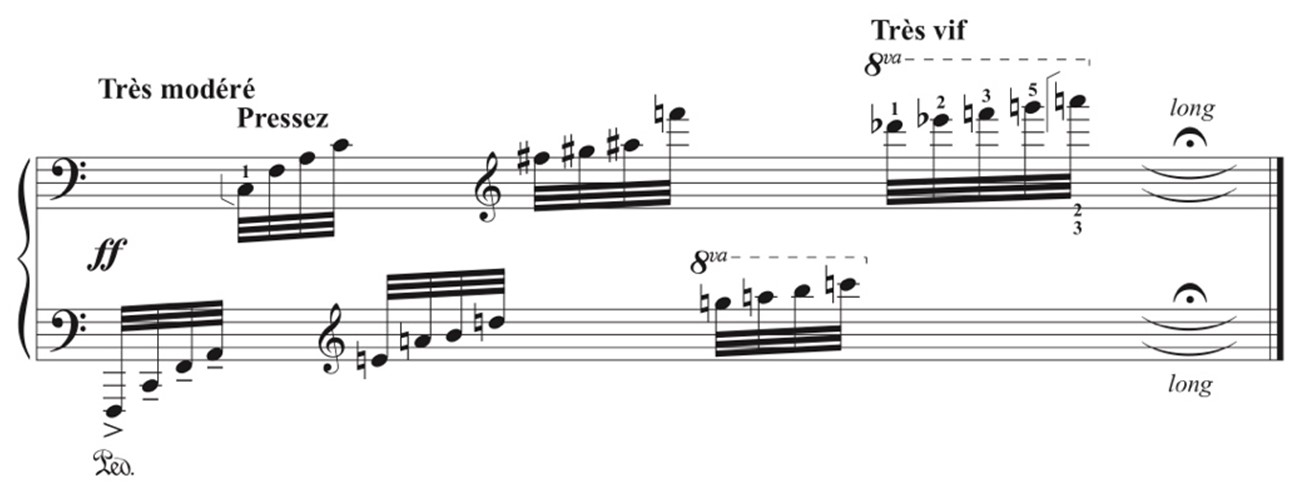

Figure 3. Carlos Marecos, A Casa do Cravo, p. 1

Note: Author’s unpublished musical score

For the notes on which I applied thrust (and oftentimes in free-fall passages on single notes), I chose either the 2nd, the 3rd or a combination of both those fingers. This practice of using more than one (strong) finger on one note actually dates back to Carl Czerny, as Luk Vaes (2009, p. 426) points out:

The very last chapter of part two (devoted to fingerings) of Czerny’s grand piano method opus 500 (1839) discusses the use of two fingers on one key. Czerny advises this technique to obtain a powerful sound and he indicates how the two fingers should be pressed together so that a strong finger can supplement a weak one. (Ex. 3.361.)

I have used similar fingerings for fast repeated or different note passages played with alternating hands, in which I combined both thrust and free-fall techniques, such as in Christopher Bochmann’s Essay VIII (cf. Telles, 2020).

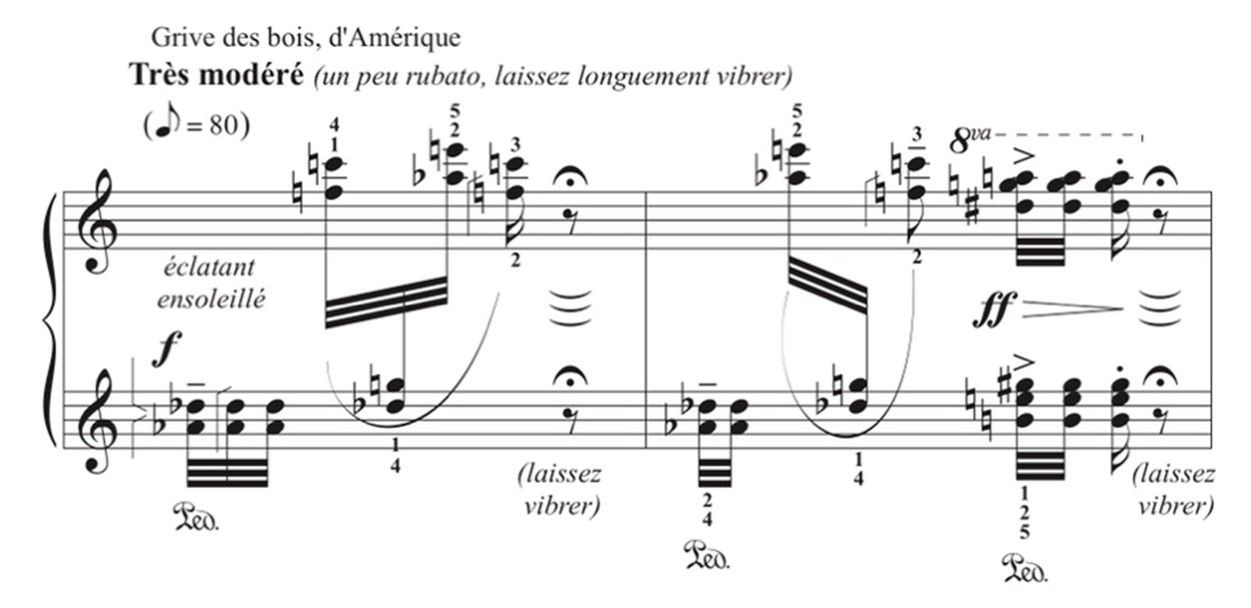

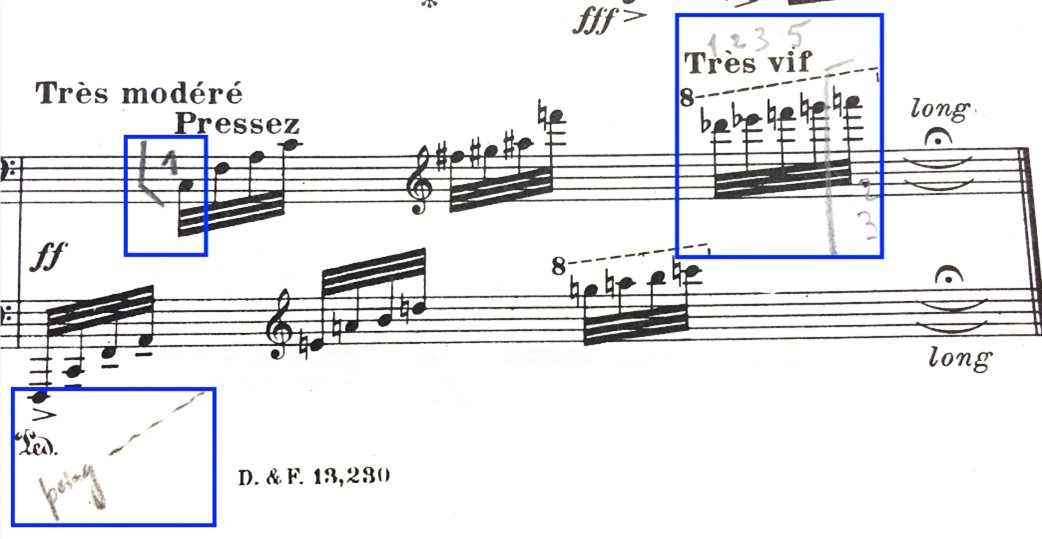

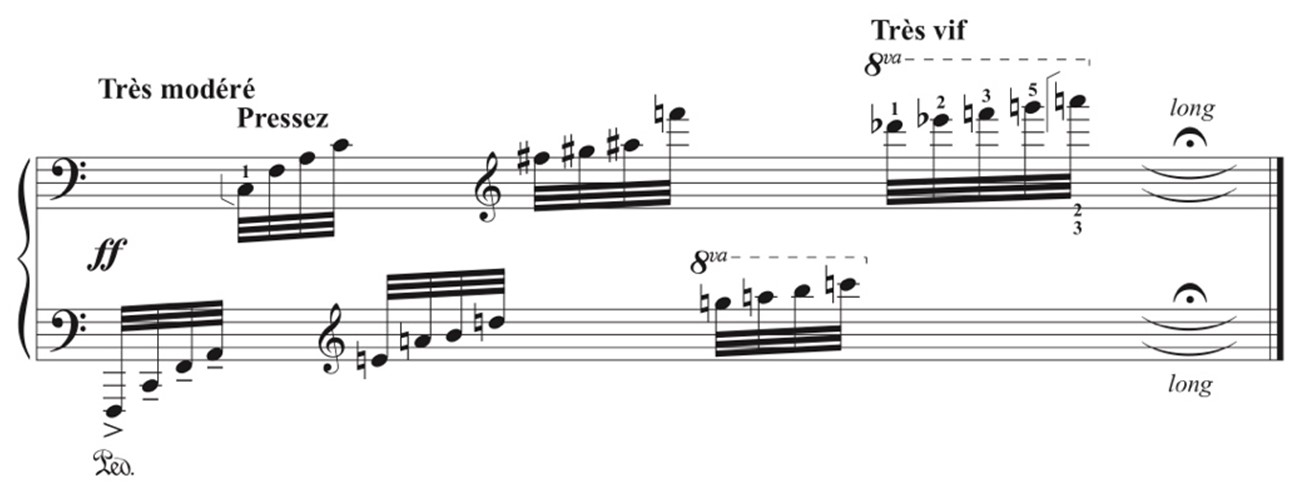

However, in certain cases, in rather fast displacements or especially when searching for a specific “ringing bells” tone quality, I replace the described fingering by the use of the fist, a technique I learned from Yvonne Loriod-Messiaen, with whom I was very fortunate to work privately in the years 1999-2001[9]. That technique allows for greater precision and sureness in utilizing free-fall, especially on black keys or clusters. Several examples may be drawn from Messiaen’s own work: the beginning of the great piano solo cadenza in Oiseaux exotiques (Figs. 4 and 5), in which Loriod advised to use the right fist in the highest note of the A flat-D flat interval, or a specific “carillon”, harmonic series-like passage in Par lui tout a été fait, from Vingt regards sur l’enfant-Jésus (Figs. 6 and 7). Using the force of gravity exclusively, this effect – which ought to be performed in a large, half-moon shaped broad gesture (as opposed to a vertical, sharp blow) – results in a large sound, full of resonances.

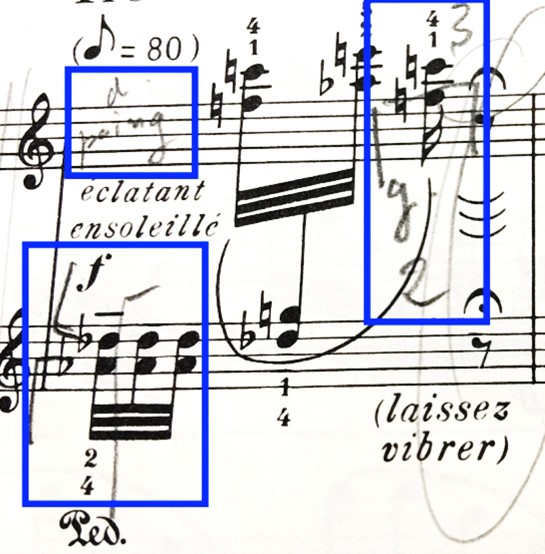

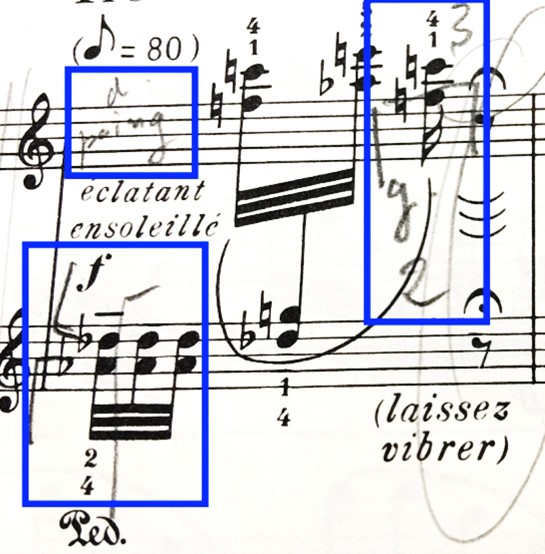

Figure 4. Olivier Messiaen, Oiseaux Exotiques (Piano part), p. 17

Note: Excerpt from the musical study score published by Universal Edition (1959, p. 3), with pencil markings by Yvonne Loriod-Messiaen in blue squares by the author

Figure 5. Olivier Messiaen, Oiseaux Exotiques (study score), p. 3

Note: Transcribed from the Universal Edition (1959)

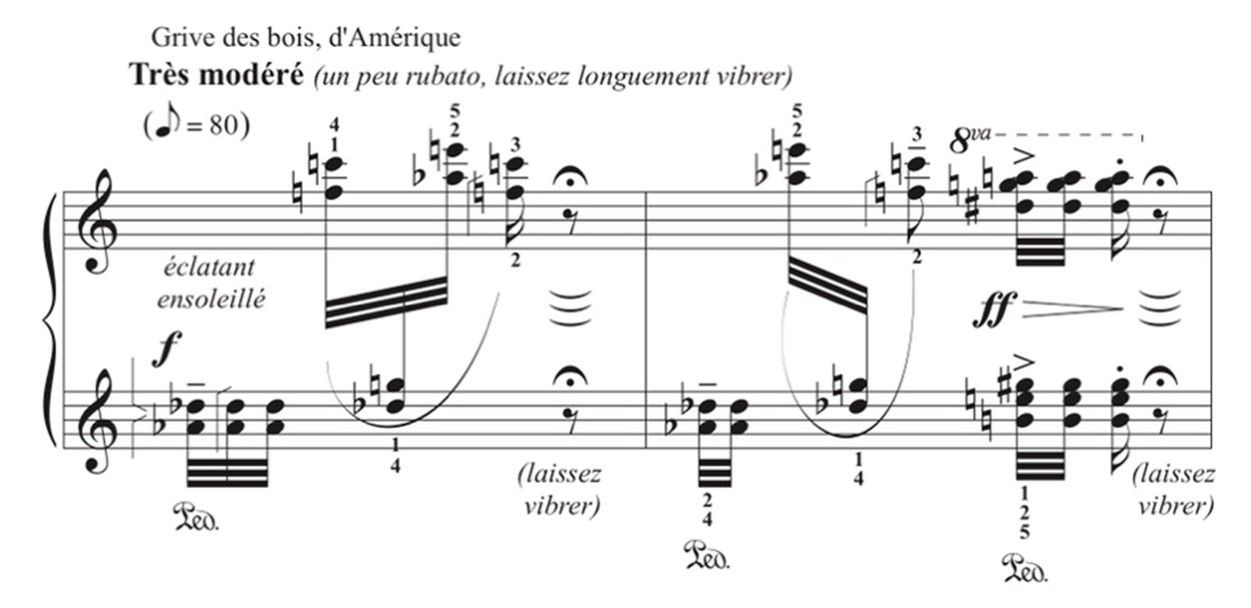

Figure 6. Olivier Messiaen, Par lui tout a étéfait, fromVingt regards sur l’enfant-Jésus, p. 45

Note: Excerpt from the musical study score published by Durand Edition, with pencil markings by Yvonne Loriod-Messiaen in blue squares by the author

Figure 7. Olivier Messiaen, Par lui tout a étéfait, from Vingt regards sur l’enfant-Jésus, p. 45

Note: Transcribed from the Durand Edition (1944)

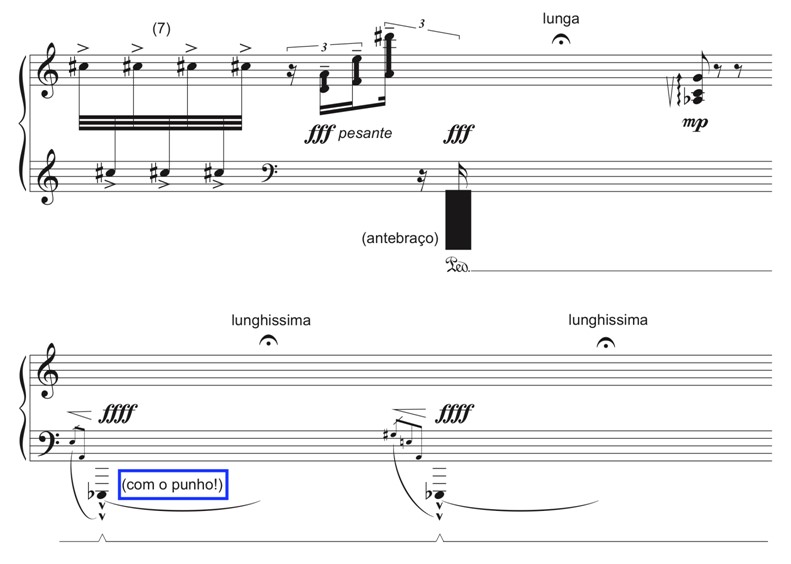

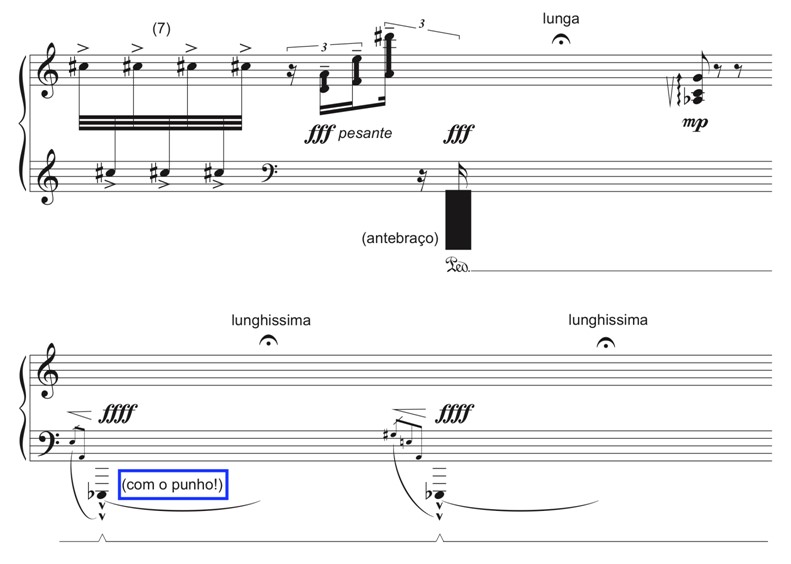

I have so often employed the fist technique, that certain composers started asking for it in the works they wrote for me; Christopher Bochmann’s Triste Tríade (2018) and Jaime Reis’ Monólito. Ébano (2019) are just two examples of that. In the first of these works, the composer intends a large, resonating sound in the isolated low E flat, on page 4 (Figure 8).

Figure 8. Christopher Bochmann, Triste Tríade, p. 4

Note: Author’s unpublished musical score, with blue square marking by the author highlighting the composer’s indication “with the fist!” (free translation)

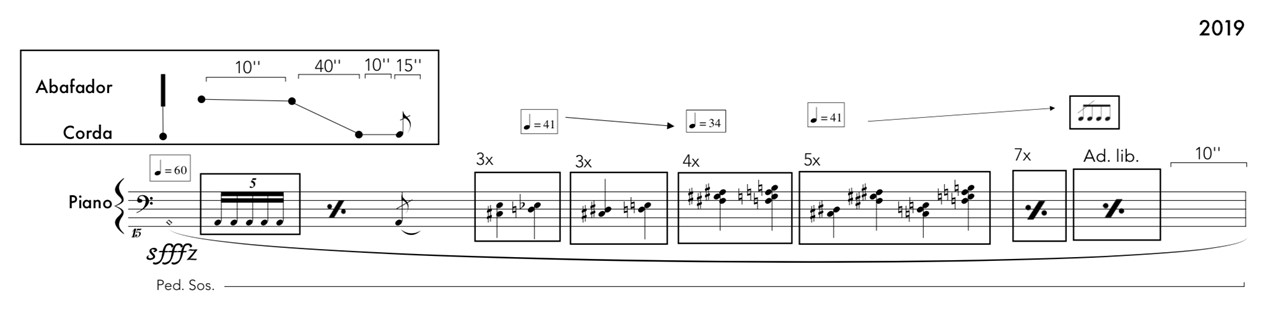

In Reis’ work, however, the physical resistance needed to perform such extended sequence of the loudest possible clusters, in a progressively faster alternating movement, is much enhanced by the unlimited use of gravity (in vertical progressively smaller gestures as speed increases) through the arms and fists, without the pianist having to use fingers, which are naturally weaker and more vulnerable to extreme stress, on the actual keys (Figure 9).

Figure 9. Jaime Reis, Monólito. Ébano, p. 1

Note: Author’s unpublished musical score

Going back to the example I’ve previously shown from Messiaen’s Le Courlis cendré, and given the extension of both hands playing a total of 11 notes in that chord’s actual note configuration, which makes “thrust” (or muscular impulse) particularly difficult (Sandor, 1995, p. 45), I have tried (with success) lifting myself from the piano stool just before the attack and using my whole upper body weight on the piano bysitting back down while simultaneously playing that chord (cf. Figure 2).

I used the same technique in Miguel Azguime’s De l’étant qui le nie, for piano and electronics, the most physically challenging piece of music I have ever played. I suggest we watch an extract from a life performance of this piece, presented at the Centro Cultural de Cascais in June 2010, with the composer operating the electronics (cf. Video 1). Please notice not only the “sitting while playing effect”, but also the amplitude of downward free-fall movements and the corresponding upward tension release movements.

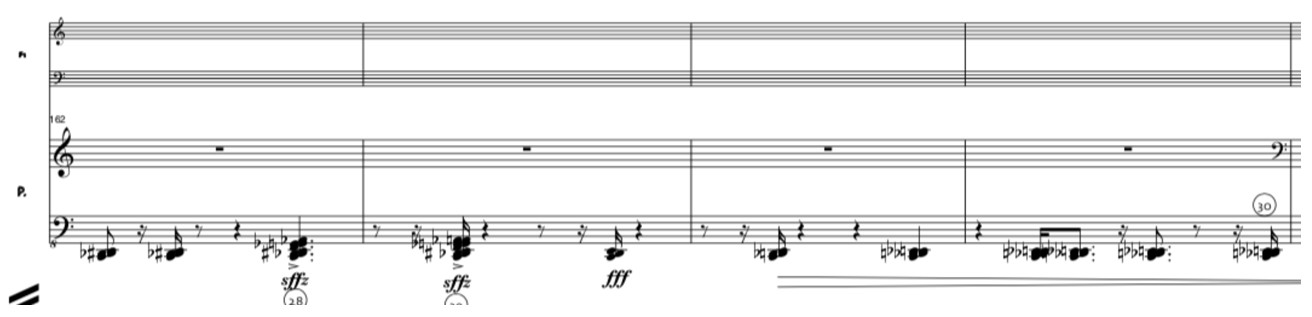

Figure 10. Miguel Azguime, De l’étant qui le nie, p. 15 (mm. 162-165)

Note: Excerpt from the CIMP / PMIC edition (2019)

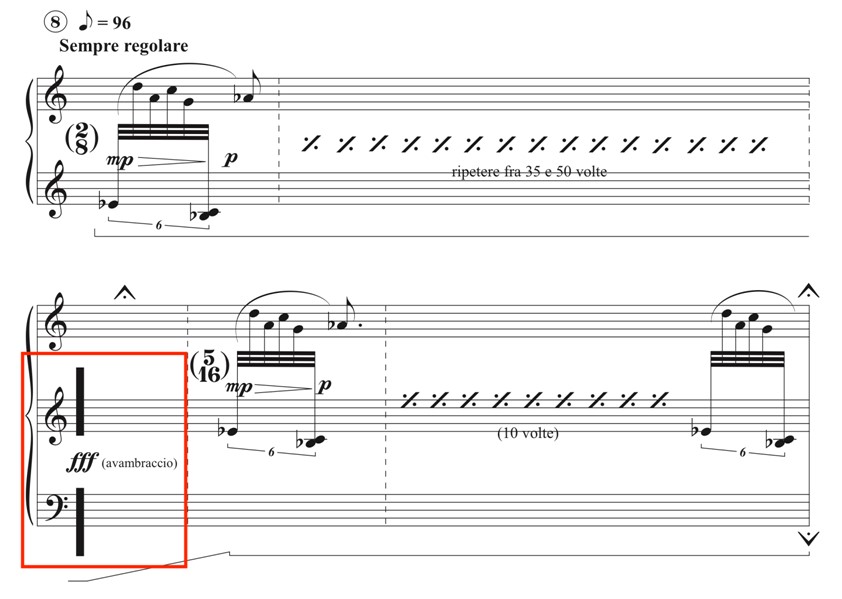

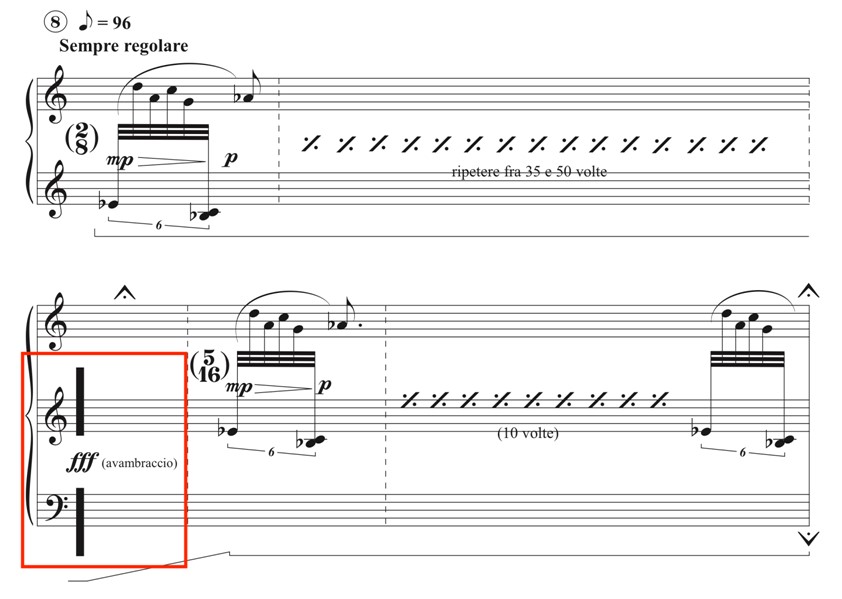

A different kind of torso engagement has been applied in my performance of Jorge Peixinho’s Estudo nº 1 – Mémoire d’une presence absente (Figure11). In that case, after a long, mesmerizing repetition of an almost hypnotic note formula, the audience was shocked by a fff cluster played at the central register of the piano by both forearms. I have achieved that effect by simply letting my whole torso fall on the keyboard over both laterally extended forearms.

Figure 11. Jorge Peixinho, Estudo I: Mémoire d’une présence absente, p. 4

Note: Transcribed from the autograph manuscript reedited by the CIMP / PMIC, with red square marking by the author

Before concluding, I’d still like to point out a strategy I have been using to provide as much anti-stiffness movement as possible when compelled by composers to perform extremely loud and fast repeated notes (in passages where hand alternation is not an option) or chords. Under such circumstances, I deliberately change the shoulders’ position several times during the passage, and move the upper torso in irregular, circular movements that help dissipate accumulated tension. That is the case in Miguel Azguime’s De l’étant qui le nie, a work already discussed above.

As I hope to have demonstrated, a healthy and sustainable approach to piano performance in an era that demands an extraordinarily broad capacity for playing extremely loud dynamic nuances, sometimes for extended periods of time, is possible if one combines the lessons learned from the pianistic tradition steming from Liszt and theorized in the beginning of the 20th century, particularly when combined with more recent, scientifically-oriented approaches. Yet, adaptations related to fingering, whole body movement and the use of less frequently employed parts of the body, such as the fiust, are useful and necessary. The emphasis that older theorizations of piano technique put on the quality of sound remains actual, but needs to be developed according to the demands of a newer and ever expanding repertoire. Correspondingly, studies about performative solutions for specific questions raised by recent repertoires must be developed by active pianists and practice-based researchers. In particular, studies related to the complex choreographies of body movements involved in the performance of contemporary works should be fostered. One should also bear in mind that an effective use of the pianist’s bodily resources in such demanding contexts needs to be complemented with efficient physical and mental conditioning strategies to be developed at the instrument and in general; these include the learning and practice of relaxation and toning activities that should be a part of a broader healthy lifestyle.

Dinâmicas extremas através dos movimentos corporais na interpretação da música para piano contemporânea

Resumo

A utilização de dinâmicas extremas e de modos de ataque que acentuam as qualidades percussivas do piano, bem como o uso de mudanças bruscas de intensidade e de registo, caracterizam uma boa parte da produção musical para piano a partir da segunda metade do século XX (Caillet, 2007). Não raramente se encontra, nesse repertório, dinâmicas que vão do pppp ao ffff, e até uma utilização sustentada de violência extrema que se manifesta na repetição de notas, de acordes, de clusters, ou outras formas de escrita musical que acentuam as nuances de fortissimo.

Ora, do ponto de vista da saúde física do pianista, sabemos que um esforço muscular de tipo repetitivo pode conduzir a lesões potencialmente graves, e que a promoção de um “movimento de qualidade” deverá, ao invés, promover um desempenho que seja “livre, expressivo e seguro” (Mark, 2003, p. 05).

Numerosas fontes sobre técnica pianística propõem soluções para o conjunto dos problemas colocados pelo repertório pianístico canónico, que se estende da segunda metade do século XVIII às primeiras décadas do século XX, mas até as fontes mais recentes têm como base repertórios desfasados do nosso tempo cronológico (Chiantore, 2019, pp. 700-702).

Deste modo, tomando como ponto de partida as questões consensuais da técnica pianística, e apoiando-me igualmente na minha própria experiência prática de intérprete que se consagra à música para piano do nosso tempo, proponho um itinerário através de diversas obras que apelam a nuances extremas, a partir das quais traçarei um repertório de movimentos que me permitiram gerir esses repertórios sem lesões ao longo de uma carreira de mais de duas décadas.

A utilização de dinâmicas extremas e de modos de ataque que acentuam as qualidades percussivas do piano, assim como as mudanças abruptas de intensidade e registo, caracterizam muita da música escrita para piano durante a segunda metade do século XX. Não é raro encontrar, nesse repertório, dinâmicas que vão do pppp ao ffff,[10] e até um uso sustentado de violência extrema que se manifesta na repetição de acordes, clusters, ou outras formas de escrita que acentuam as nuances de fortissimo. Estes aspectos integram a tendência geral dos compositores mais recentes para desenvolver o pleno potencial sonoro e técnico do piano, ao mesmo tempo que alargam o seu espaço acústico e privilegiam certas rupturas no discurso musical, em oposição ao esquema frásico clássico de “arsis/acento/tese” (Caillet, 2007, p. 55). Catherine Vickers (2008, p. 2) atribui a Karlheinz Stockhausen a declaração de que “as dinâmicas em música são absolutamente fracas e encontram-se por desenvolver”, e afirma que “Já desde 1967 ele apelava ao uso de um ‘tonómetro’ com uma coluna de luz com a qual os músicos poderiam controlar as suas dinâmicas.”

A esta mudança estética corresponde um “pico de poder” na construção dos pianos, o qual, de acordo com Kreidy (2012, p. 65) terá ocorrido durante a primeira década do século XXI, embora “as características organológicas do instrumento [estivessem] consolidadas” desde o início do século anterior (Chiantore, 2019, p. 702). Ao mesmo tempo, de acordo com Martingo (2018, p. 146),

Martingo afirma em seguida que “[…] a execução musical apresenta historicamente uma extensão contínua do aparelho corporal, cujo domínio das competências motoras finas implica uma disciplina corporal, repetição, e o bónus diferido que configuram uma prática racionalizada com um alto nível de auto-controle” (Martingo, 2018, p.148).

Pode parecer bastante surpreendente notar que, enquanto se desenrolava uma expansão dos meios corporais associados aos repertórios e técnicas de piano ao longo de todo o século XX, a teorização sobre movimentos corporais, ou técnicas de piano, diminuiu a partir de 1929, data em que foi publicada a obra The Physiological Mechanics of Piano Technique, de Otto Rudolf Ortmann. Por outro lado, a maioria dos trabalhos sobre a técnica pianística oferece soluções para os problemas colocados pela execução do repertório pianístico padrão, que se estendeu desde a segunda metade do século XVIII até às primeiras décadas do século XX (Chiantore, 2019, pp. 700-702), baseando-se principalmente em repertórios defasados do nosso próprio tempo cronológico.

Contudo, a proliferação de livros e tratados sobre técnica pianística no início do século XX, alguns dos quais citarei brevemente nos meus comentários abaixo,[11] pode ser vista como uma resposta natural à revolução operada pela música para piano de Franz Liszt. Segundo Chiantore (2019, p. 345),

A técnica de piano de Liszt revela uma variedade no toque até então desconhecida. Ainda estamos muito longe da sistematização de um Tobias Matthay ou de um Rudolf Maria Breithaupt, pois Liszt desde o início que se focou sobre as figurações, e não sobre o processo de convertê-las em som.

Essas figurações incluíam oitavas (simples e quebradas), tremolos (em notas simples e duplas, incluindo trilos e notas repetidas), notas duplas e notas simples. A sua realização física dependia de um conjunto de “mecanismos fundamentais”, como a rotação do braço ou o peso (Chiantore, 2019, p. 346). Ainda nas palavras de Chiantore,

É impossível saber se Liszt percebia essa distinção conceptual entre fórmulas escritas e recursos musculares com a mesma clareza que encontramos nalguns tratados do século XX, mas não há dúvida que a sua própria produção foi a primeira a permitir e fomentar propostas desse tipo. (Chiantore, 2019, pp. 346-347)

Quando William Mason, discípulo de Liszt, se propôs elaborar sobre a natureza da técnica de piano de seu mestre, nos quatro volumes do seu Touch and Technic, or the Technic of Artistic Piano Playing by means of a New Combination of Exercice-Forms and Method of Practice, op. 44 (Mason, 1892),[12] considerou três tipos básicos de movimentos: toques de dedos, toques de mão e toques de braço (Chiantore, 2019, p. 348).

Os toques de braço são particularmente importantes, pois combinam os dois elementos fundamentais, peso e impulsos musculares, que vieram desde então a ser considerados “as duas forças que regem as acções pianísticas – a gravidade e a energia cinética produzida pelo aparelho muscular” (Chiantore, 2019, p. 352). Além disso, Liszt estava plenamente consciente do “balouçar”, ou movimento ascendente do braço resultante da batida anterior das teclas, a que Adolph Kullak chamou Ausschwung (Kullak, 1855).

Ao combinar esses gestos essenciais do braço para cima e para baixo numa variedade infinita de possibilidades, a técnica pianística derivada de Liszt permitiu aos intérpretes “manipularem […] organicamente […] trechos dificílimos” (Chiantore, 2019, p. 352), fomentando simultaneamente o desenvolvimento de modulações tímbricas até então inconcebíveis.

Num trabalho seminal publicado em 1995, On piano playing: motion, sound and expression, Gyorgy Sandor associa os mesmos princípios fundamentais à dinâmica, afirmando que a produção de volume na execução do piano depende apenas da “velocidade com que o martelo atinge a corda” (Sandor, 1995, p. 6). Afirma ainda que:

Para mobilizar o aparato instrumental e gerar a velocidade desejada nos martelos, há unicamente duas fontes de energia disponíveis: a força da gravidade […] e a energia muscular. […] Essas forças, e suas inter-combinações, fornecem todas as fontes de energia disponíveis para activar todo o equipamento instrumental. […] Cabe-nos a nós determinar quando devemos utilizar exclusivamente a força da gravidade, quando devemos usar exclusivamente a energia muscular e quando e como devemos combinar ambas. (Sandor, 1995, p. 7)

Depois de prevenir contra a futilidade de aplicar pressão extra sobre as teclas depois de as tocar, Sandor conclui:

O peso, por si só, é também pouco útil, a menos que seja posto em movimento. […] A força muscular é apenas útil para gerar velocidade nos martelos, não como energia gasta estaticamente. A activação simultânea e prolongada de um conjunto antagónico de músculos […] é improdutiva e, apesar de gerar uma vigorosa sensação de energia e tensão no braço, é totalmente supérflua, e deve por isso ser evitada. Produz apenas imobilidade e rigidez, o que resulta num som medíocre. A conclusão inevitável é que a técnica deve ser dirigida para colocar os martelos em movimento, usar a força da gravidade e despender uma quantidade mínima e eficiente da nossa própria energia muscular. Tanto um máximo fortissimo como o pianissimo mais leve podem ser produzidos por esses procedimentos sem qualquer esforço. (Sandor, 1995, p. 8)

Sandor avisa ainda sobre as limitações da produção do som no instrumento, afirmando que

[…] o piano, tal como qualquer outro instrumento musical, é limitado na quantidade de som que pode produzir e na capacidade de resposta do seu mecanismo. […] Sob circunstância alguma se deve esforçar ao tocar fortissimo! Embora o piano possa produzir um volume tremendo, as suas sonoridades máximas serão atingidas não quando a quantidade máxima de energia for despendida, mas quando os limites de elasticidade do seu mecanismo forem atingidos, embora não ultrapassados. (Sandor, 1995, pp. 14-15)

Lev Oborin, por sua vez, destaca dois aspectos fundamentais: por um lado, afirma que o “desenvolvimento bem-sucedido da técnica” depende antes de tudo da “liberdade psicológica e física” (Oborin, 2008, p. 70). Ele define esta última da seguinte forma: “A sensação de liberdade que refiro significa que se encontram envolvidos no meu trabalho apenas os músculos essenciais, e tocar piano baseia-se de facto no rápido e sucessivo distender e relaxar dos músculos” (Oborin , 2008, pág. 71). Por outro lado, realça a importância do envolvimento de todo o aparelho de braço, mão e dedos ao tocar. Segundo ele, “o som é obtido no piano de várias maneiras, por vários movimentos, dependendo do carácter da música, mas basicamente deve ser criado usando todo o braço, correctamente coordenado”. (Oborin, 2008, p. 73)

A ideia de se poder obter um volume elevado através do envolvimento de todo o tronco superior é expressa por Grigorii Prokofiev, pianista soviético que estudou com Konstantin Igumnov no Conservatório de Moscovo: “Num grande forte a energia inicial fundamental até vem do tronco – os elos restantes do braço e da mão são meros transmissores de energia. Aqui são accionados todos os elos da mão, braço, ombro e tronco” (Igumnov, 2008, p. 81). Por seu turno, Joseph Lhevinne afirmou: “É claro que a força, a força física real, é necessária para tocar muitas das grandes obras-primas que exigem um tom potente; mas há uma maneira de transmitir essa força ao piano para que o instrumentista economize a sua própria força” (Lhevinne, 1972, p. 29). Ele introduz a seguir dois elementos distintivos: a postura e o papel dos pulsos como “amortecedores”.

Ao comentar um esboço de Anton Rubinstein tocando piano, Lhevinne nota que: “[…] Em todas as suas passagens em forte ele usava o peso do corpo e dos ombros” (Lhevinne, 1972, p. 29). E continua assinalando que, se não há ruído de “batida” nas passagens de maior volume de Rubinstein, isso explica-se porque os seus “pulsos estavam sempre livres de rigidez nessas passagens e ele tirava partido do amortecedor natural no pulso que todos possuímos” (Lhevinne, 1972, p. 31). A sua conclusão realça a importância da qualidade do som na execução de dinâmicas de volume elevado: “Existe um princípio acústico envolvido em tocar nas teclas. Se a batida for repentina, dura, brutal, as vibrações das cordas parecem ser muito menos penetrantes do que quando os martelos são operados de modo que as cordas são ‘tocados’ como um sino.” (Lhevinne, 1972, p. 32)

Para resumir, devemos notar que, desde a época de Franz Liszt, a ênfase tem sido colocada na conectividade entre os movimentos dos dedos, das mãos e dos braços, assumindo estes um papel preponderante através de infinitas combinações de micro-movimentos que dependem tanto da força de gravidade como dos impulsos musculares, os quais por sua vez geram movimentos ascendentes e descendentes. A liberdade de movimento, em sentido mais amplo, que daí resulta tem sido aclamada por pianistas, professores e teóricos, associados particularmente, mas não exclusivamente, à chamada escola russa de piano, tais como Lev Oborin, Grigorii Prokofiev, Joseph Lhevinne, Arthur Rubinstein e outros, para os quais a execução de dinâmicas de volume extremamente elevado foi considerada mais eficaz quando se mobiliza o tronco por inteiro; a qualidade do som, mesmo nessas circunstâncias extremas, era considerada indispensável e teria de ser assegurada pelo pianista, que deveria evitar "bater" no paino a favor de uma abordagem comparável ao “toque de sinos”. Da mesma forma, apoiando-se numa explicação completa das questões anatómicas relevantes, Gyorgy Sandor salientou que a dinâmica fff depende apenas da velocidade de descida do martelo, que por sua vez é condicionada pelo “peso” do braço do pianista e pelos impulsos musculares; advertiu igualmente que o próprio instrumento tem limitações físicas no que respeita às dinâmicas extremas.

Do ponto de vista do bem-estar físico do pianista, sabemos que um esforço muscular repetitivo pode resultar em lesões potencialmente graves, e que a promoção de um “movimento de elevada qualidade” pode, pelo contrário, promover uma execução “livre, expressiva e segura” (Mark, 2003, p. 5). Esse movimento de elevada qualidade, que pode ser atingido através do desenho, ensaio e execução de uma coreografia específica para cada peça musical, com base em movimentos parciais menores, corresponde em grande parte à noção de “liberdade” de tocar a que aludi anteriormente.

De acordo com Thomas Mark (2003, pp. 6-7),

Cada peça musical consiste numa série de notas diferentes de qualquer outra peça musical […], por isso cada peça exige a sua própria série de movimentos. É oportuno insistir, como fazem alguns professores, que o movimento deve ser tão complexo quanto a música.

Movimento complexo e variado é de facto aquilo a que assistimos em intérpretes livres. Mas geralmente não é o que vemos em pianistas lesionados. […] O movimento estereotipado torna a execução pianística mais repetitiva do que o necessário e é uma causa comum de lesões.

Por outro lado, Mark (2003, p. 130) alerta para o facto de que “muitos pianistas usam força excessiva, o que causa lesões. […] Também pode contribuir para um tom áspero e inexpressivo.” Nesse sentido, o autor reflecte as observações de Sandor e Lhevinne, a partir de uma perspectiva anatómica e fisiológica.

Parece de facto existir uma correspondência muito forte entre as perspectivas recentes e cientificamente informadas de Mark (2003), Sandor (1995) e Fink (1992), e os preceitos com base na prática dos pianistas, professores de piano e teóricos de épocas anteriores. No entanto, como já referi, a maioria delas ou aborda, ou se baseia, exclusivamente, nos repertórios de entre o século XVIII e o início do século XX, excluindo toda uma gama de música para piano escrita desde 1950 até o século XXI, a qual, como já foi referido, pode ser extremamente exigente no que diz respeito a dinâmicas fortes e modos de ataque. Ao mesmo tempo, devemos notar que a maioria dos livros que tratam de questões contemporâneas de interpretação pianística não abordam especifica ou profundamente a questão das dinâmicas extremas. Catherine Vickers (2008, pp. 3-11), por exemplo, sugere uma série de exercícios para desenvolver a diferenciação dinâmica, mas não oferece conselhos sobre como obter tais efeitos dinâmicos, inclusive os extremos. Alan Shockley (2018), por sua vez, elenca um número significativo de técnicas e recursos pianísticos contemporâneos, mas também não aborda as especificidades dos movimentos corporais envolvidos na obtenção do som correspondente a essas técnicas e recursos. Uma série de teses e dissertações académicas (por exemplo, Vaes, 2009; Proulx, 2009; Ishii, 2005; Hudicek, 2002) fornecem uma visão interessante e extensa sobre as técnicas mais amplas do piano, mas deixam de lado as questões que pretendo elucidar neste estudo.

Como pode um pianista lidar com essas exigências mantendo simultaneamente uma abordagem saudável e sustentável à execução pianística? Serão os conselhos compilados nas linhas acima úteis para um pianista do século XXI que terá de executar obras extenuantes de Pierre Boulez, György Ligeti, Karlheinz Stockhausen, Iannis Xenakis[13] e tantos outros compositores? Em caso afirmativo, será necessária alguma adaptação que possa actualizar a técnica do piano tal como foi herdada da tradição Lisztiana, especificamente no que diz respeito a dinâmicas de volume extremamente elevado?

Tomando como ponto de partida os grandes temas consensuais da técnica pianística evocados acima, e confiando na minha própria experiência prática como intérprete dedicada à música para piano do nosso tempo, proponho um itinerário através de diferentes obras que recorrem a nuances dinâmicas extremas, a partir das quais irei desenhar um repertório de movimentos que me permitiram gerir, sem lesões, a minha actividade pianística ao longo de uma carreira que se estende por mais de duas décadas.

Comecemos pelo uso da força da gravidade. Gyorgy Sandor (1995, pp. 41-51) oferece instruções detalhadas sobre o que ele chama de "queda livre" e sugere exercícios específicos para desenvolver essa técnica. Afirma: "Não há dúvida que as maiores sonoridades do piano podem ser alcançadas pelo movimento de queda livre". (Sandor, 1995, p. 46). A queda livre supõe três fases: levantar as estruturas envolvidas (dedos, mão, antebraço ou braço inteiro), deixá-las cair de acordo com a força da gravidade, e aterrar. Como a queda livre está dependente do tempo e da distância para que o processo de aceleração se possa desenrolar, aplica-se apenas a "passagens em andamento moderado" (Sandor, 1995, p. 45).

Utilizei o aparelho inteiro do braço em queda livre quando pretendia produzir um potente fff em Le Courlis cendré de Olivier Messiaen (de Catalogue d'Oiseaux, Vol. 7). De facto, na página 16, o compositor apela a essa nuance, que ele define como "espessa", orientando o pianista para "tocar a partir de cima", com "ataques profundos".

Figura 1. Olivier Messiaen, Le Courlis cendré (de Catalogue d’Oiseaux, Vol. 7), p. 16

Nota: Transcrito da edição de Alphonse Leduc[14]

Mais à frente, na mesma peça, Messiaen dá a indicação de uma nuance fff num motivo que retrata a sirene de um farol à noite, contrastando nitidamente com os sons da natureza envolvente que a peça evoca. De modo a aumentar a altura da queda livre e a aplicar todo o tronco ao fazer soar a nota mais baixa do piano nesse motivo, optei por tocá-la não com a mão esquerda, como seria de esperar, mas com a mão direita; utilizei o terceiro dedo devido ao seu alinhamento central com a mão e o braço, ligeiramente curvado e caindo de forma totalmente vertical, como sugerido por Sandor (1995, p. 46).

Figura 2. Olivier Messiaen, Le Courlis cendré (de Catalogue d’Oiseaux, Vol. 7), p. 17

Nota: Transcrito da edição de Alphonse Leduc

Note-se que ambas as passagens que usei para exemplificar movimentos puros de queda livre se desenrolam em andamento lento, o que permite a aplicação dessa técnica. No entanto, em passagens em que se pede que sejam tocadas notas diferentes, nas quais existe o risco de se tocar as teclas erradas, a técnica de queda livre deve ser substituída pela abordagem de "impulsão", a qual, de acordo com Sandor (1995, p. 108),

[...] é executada unicamente por músculos activos, e nem a força da gravidade nem o peso são utilizados. Em vez de levantar os braços, as mãos e os dedos, e sujeitá-los à aceleração gradual da força da gravidade, colocamos os dedos na superfície das teclas e empurramos as teclas para baixo com uma súbita e instantânea contracção de alguns dos músculos mais fortes do corpo e dos braços [...]

Adoptei essa abordagem na minha interpretação de A casa do cravo, de Carlos Marecos (2019), obra para piano e electrónica, na qual, embora o andamento seja moderado, algumas alterações de notas são suficientemente rápidas para gerar um risco potencial de erro se for aplicada a queda livre. Claro que a utilização de uma tal contracção muscular "instantânea e súbita" exige uma correspondente libertação de tensão, razão pela qual tenho seguido cada ataque por um grande ressalto, sob a forma de um movimento rápido para cima de todo o braço (cf. figura 3).

Figura 3. Carlos Marecos, A Casa do Cravo, p. 1

Nota: Edição do compositor

Para as notas sobre as quais apliquei impulsão (e frequentemente, também, nas passagens em queda livre sobre notas individuais), escolhi ou o 2º, o 3º ou uma combinação desses dois dedos. Esta prática de utilizar mais do que um dedo (forte) numa única nota remonta na verdade a Carl Czerny, como aponta Luk Vaes (2009, p. 426):

O último capítulo da segunda parte (dedicado à dedilhação) do grandioso método de piano de Czerny, opus 500 (1839) discute a utilização de dois dedos numa só tecla. Czerny aconselha o uso desta técnica para obter um som potente e indica como os dois dedos devem ser pressionados juntos para que um dedo forte possa complementar um outro fraco. (Ex. 3.361).

Utilizei dedilhações semelhantes para passagens de notas rápidas, repetidas ou diferentes, tocadas com mãos alternadas, nas quais combinei técnicas de impulsão e de queda livre, por exemplo na Essay VIII, de Christopher Bochmann (cf. Telles, 2020).

No entanto, em certos casos, em deslocações rápidas ou sobretudo quando procuro uma qualidade sonora semelhante ao som de sinos, substituo a dedilhação descrita pelo uso do punho, uma técnica que aprendi com Yvonne Loriod-Messiaen, com quem tive o grande privilégio de trabalhar em privado nos anos de 1999-2001.[15] Esta técnica permite uma maior precisão e segurança na utilização da queda livre, especialmente nas teclas pretas ou clusters. Vários exemplos podem ser extraídos da própria obra de Messiaen: o início da grande cadência a solo para piano em Oiseaux exotiques (Figs. 4 e 5), na qual Loriod me aconselhou a usar o punho direito na primeira nota do intervalo Mi Bemol – La Bemol ou uma passagem específica semelhante a um "carrilhão", baseada na série de harmónicos, em Par lui tout a été fait, de Vingt regards sur l'enfant Jésus (Figs. 6 e 7). Usando exclusivamente a força da gravidade, este efeito - que deve ser executado num gesto amplo, em forma de meia-lua (em contraste com um golpe vertical e agudo) - resulta num som amplo, cheio de ressonâncias.

Figura 4. Olivier Messiaen, Oiseaux Exotiques (parte para piano), p. 17

Nota: Excerto da partitura de estudo publicada pela Universal Edition (1959, p. 3), com anotações a lápis de Yvonne Loriod-Messiaen dentro dos quadrados azuis acrescentados pela autora

Figura 5. Olivier Messiaen, Oiseaux Exotiques (partitura de estudo), p. 3

Nota: Transcrito da Universal Edition (1959)

Figura 6. Olivier Messiaen, Par lui tout a été fait,de Vingt regards sur l’enfant Jésus, p. 45

Nota: Excerto da partitura de estudo publicada pela Edition Durand (1944), com anotações a lápis de Yvonne Loriod-Messiaen dentro dos quadrados azuis acrescentados pela autora

Figura 7. Olivier Messiaen, Par lui tout a été fait, de Vingt regards sur l’enfant Jésus, p. 45

Note: Transcrito da Edição Durand (1944)

Utilizei tão frequentemente a técnica do punho, que certos compositores começaram a pedi-la nas obras que escreveram para mim; Triste Tríade, de Christopher Bochmann (2018), e Monólito. Ébano, de Jaime Reis (2019), são apenas dois exemplos disso. Na primeira destas obras, o compositor pretende obter um som grande e ressonante no Mi Bemol grave isolado, na página 4 (Figura 8).

Figura 8. Christopher Bochmann, Triste Tríade, p. 4

Nota: Edição do compositor, com anotação a autora no quadrado azul

Na obra de Reis a resistência física necessária para realizar uma sequência tão extensa de clusters com o volume de som mais elevado possível, num movimento alternado e progressivamente mais rápido, é muito reforçada pelo uso ilimitado da gravidade (em gestos verticais progressivamente mais pequenos à medida que a velocidade aumenta) através dos braços e punhos, sem que o pianista tenha de usar os dedos, que são naturalmente mais fracos e mais vulneráveis ao stress extremo, sobre as teclas (Figura 9).

Figura 9. Jaime Reis, Monólito. Ébano, p. 1

Nota: Edição do compositor

Voltando ao exemplo anterior, do Courlis cendré, de Messiaen, e dada a extensão de ambas as mãos tocando um total de onze notas na configuração efectiva desse acorde, que torna a "impulsão" (ou impulso muscular) particularmente difícil (Sandor, 1995, p. 45), tentei (com sucesso) levantar-me do banco do piano imediatamente antes do ataque e usar todo o peso do meu corpo sobre o piano, sentando-me de novo enquanto tocava simultaneamente esse acorde (cf. Figura 2).

Utilizei a mesma técnica no De l'étant qui le nie, para piano e electrónica, de Miguel Azguime, a obra fisicamente mais desafiante que alguma vez toquei. Sugiro que vejamos um extracto de uma interpretação ao vivo dessa peça, apresentada no Centro Cultural de Cascais em Junho de 2010, com o compositor a operar a electrónica (cf. Vídeo 1). Notem por favor não apenas o "efeito de sentar-se enquanto se toca", mas também a amplitude dos movimentos de queda livre para baixo e os correspondentes movimentos de libertação de tensão para cima.

Figura 10. Miguel Azguime, De l’étant qui le nie, p. 15 (mm. 162-165)

Nota: Excerto da edição CIMP / PMIC (2019)

Apliquei um tipo diferente de envolvimento do tronco na minha execução do Estudo I: Mémoire d'une présence absente, de Jorge Peixinho (Figura 11). Neste caso, após uma longa e encantatória repetição de uma fórmula quase hipnótica de notas, o público ficou chocado com um cluster de fff tocado no registo central do piano. Obtive esse efeito simplesmente deixando todo o meu tronco cair no teclado, sobre ambos os antebraços lateralmente estendidos.

Figura 11. Jorge Peixinho, Estudo I: Mémoire d’une présence absente, p. 4

Nota: Transcrito do manuscrito autógrafo reeditado pelo CIMP / PMIC, com marcação a quadrado vermelho da autora

Antes de concluir, gostaria ainda de salientar uma estratégia que tenho vindo a utilizar para eliminar ao máximo a rigidez quando compelida pelos compositores a executar notas ou acordes repetidos, de volume extremamente elevado (em passagens onde alternar as mãos não é uma opção). Em tais circunstâncias, mudo deliberadamente a posição dos ombros várias vezes durante a passagem, e movo a parte superior do tronco em movimentos irregulares e circulares que ajudam a dissipar a tensão acumulada. É o caso do De l'étant qui le nie, de Miguel Azguime, uma obra já discutida acima.

Como espero ter demonstrado, é possível adoptar uma abordagem saudável e sustentável na execução de música para piano, numa época que exige a realização de nuances dinâmicas de volume extremamente elevado, por vezes por extensos períodos de tempo, se combinarmos as lições da tradição pianística proveniente de Liszt e teorizada no início do século XX com abordagens mais recentes e cientificamente orientadas. No entanto, as adaptações relacionadas com a dedilhação, o movimento do corpo inteiro e a utilização de partes do corpo menos convencionais, tais como o punho, são também úteis e necessárias. A ênfase na qualidade do som permanece actual, mas precisa de ser perspectivada à luz das exigências de um repertório mais recente e em constante expansão. Do mesmo modo, estudos sobre soluções performativas para questões específicas levantadas por repertórios recentes devem ser desenvolvidos por pianistas no activo e por investigadores baseados na prática. Em particular, devem ser fomentados os estudos relacionados com as coreografias complexas dos movimentos corporais envolvidos na execução de obras contemporâneas. Também se deverá ter em linha de conta que uma utilização eficaz dos recursos corporais do pianista em contextos tão exigentes precisa de ser complementada com estratégias eficientes de condicionamento físico e mental para serem desenvolvidas na execução instrumental e em geral; estas incluem a aprendizagem e prática de actividades de relaxamento e tonificação que devem fazer parte de um estilo de vida saudável mais amplo.

Bibliography/Bibliografia

Albeniz, I. (1961). Fête Dieu à Séville. Iberia (1er Cahier), 20-45. Madrid: Union Muical Española.

Azguime, M. (2019). De l'étant qui le nie. Parede: CIMP / PMIC.

Bochmann, C. (2018). Triste Tríade (Unpublished Musical Score). Évora.

Caillet, L. (2007). Les Exigences du piano contemporain. In D. Pistone (Ed.), Pianos & Pianistes dans la France d'aujourd'hui (Série Conférences et Séminaires ed., Vol. 29, pp. 55-65). Paris: Université de Paris - Sorbonne | Observatoire Musical Français.

Chiantore, L. (2019). Tone Moves: A History of Piano Technique. Barcelona: Musikeon Books.

Fink, S. (1992). Mastering Piano Technique: A Guide for Students, Teachers and Performers.Portland: Amadeus Press.

Fonseca, S. I. (2004). As Escolas de Piano Europeias: Tendências da Interpretação Pianística no Século XX. Évora: Universidade de Évora.

Hudicek, L. (2002). Off key : a comprehensive guide to unconventional piano techniques. Off key : a comprehensive guide to unconventional piano techniques. College Park: University of Maryland College Park.

Igumnov, K. (2008). Some Technical Observations. In C. Barnes (Ed.), The Russian Piano School: Russian Pianists and Moscow Conservatoire Professors on the Art of the Piano (C. Barnes, Trans., 2 ed., pp. 78-83). London: Kahn & Averill.

Ishii, R. (2005). The Development of Extended Piano Techniques in Twentieth-Century American Music. Tallahassee: Florida State University.

Kreidy, Z. (2012). Les avatars du piano. Paris: Beauchesne.

Kullak, A. (1855). Die Kunst des Anschlags: Ein Studienwerk für vorgerückterer Klavier-spieler und Leitfaden für Unterrichtende, op. 17. Leipzig: Hoffmeister.

Lechner-Reydellet, C. (2008). Ana Telles: Témoignage sur Yvonne Loriod-Messiaen. In C. Lechner-Reydellet, Messiaen, L'empreinte d'un géant (pp. 93-103). Paris: Séguier.

Lhevinne, J. (1972). Basic Principles in Pianoforte Playing. New York: Dover.

Marecos, C. (2019). A Casa do Cravo (Unpublished Musical Score). Lisbon.

Mark, T. (2003). What every pianist needs to know about the body. Chicago: GIA Publications.

Martingo, Â. (2018). Um corpo elíptico: a expressão e o gesto sob o signo da civilização. In A música e o corpo (pp. 145-162). Lavra: Letras & Coisas.

Mason, W. (1892). Touch and Technic, or the Technic of Artistic Piano Playing by means of a New Combination of Exercice-Forms and Method of Practice, op. 44. Philadelphia: Th. Pressler.

Messiaen, O. (1944). Par lui tout a été fait. Vingt regards sur l’enfant-Jésus. Paris: Editions Durand.

Messiaen, O. (1959). Oiseaux exotiques. London: Universal Edition.

Messiaen, O. (1964). Le Courlis Cendré. Catalogue d'Oiseaux, Vol. 7. Paris: Alphonse Leduc.

Oborin, L. (2008). Some principles of pianoforte technique. In C. Barnes (Ed.), The Russian Piano School: Russian Pianists and Moscow Conservatoire Professors on the Art of the Piano (C. Barnes, Trans., 2 ed., pp. 68-77). London: Kahn & Averill.

Ortmann, O. R. (1929). The Physiological Mechanics of Piano Technique. London and New York: Kegan, Trench, Trubner & Co.

Peixinho, J. (n.d.). Estudo I: Mémoire d'une présence absente. Parede: CIMP / PMIC.

Proulx, J.-F. (2009). A pedagogical guide to extended piano techniques. Philadelphia: Temple University.

Reis, J. (2019). Monólito. Ébano (Unpublished Musical Score). Lisbon.

Sandor, G. (1995). On piano playing: motion, sound and expression. Belmont: Schirmer books.

Shockley, A. (2018). The contemporary piano: a performer and composer's guide to techniques and resources. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield.

Telles, A. (2020, April 23). Essay VIII: a key work in the piano output of Christopher Bochmann. Retrieved from Performance e Contexto: https://perf.esml.ipl.pt/index.php/component/k2/item/9-essay-viii-a-key-work-in-the-piano-output-of-christopher-bochmann

Vaes, L. (2009). Extended piano techniques: In theory, history and performance practice. Leiden: Leiden University.

Vickers, C. (2008). Die Hoerende Hand (Vol. 2). Mainz: Schott.

[1] These extreme markings are to be found in early 20th century works, such as Fête Dieu à Séville(composed in 1906), third piece in the first book of Isaac Albeniz’ Iberia (Albeniz, 1961).

[2] Author’s translation.

[3] Author’s translation.

[4] Author’s translation.

[5] I will focus mainly on works by prominent pianists of the so-called Russian School of Piano Playing, since, as a performer, I identify mostly with it, having been formed according to that school’s principles by pianists Tânia Achot (at Escola Superior de Música de Lisboa, Portugal, between 1991 and 1995) and Nina Svetlanova (at the Manhattan School of Music, New York, USA, from 1995 to 1999). For a comprehensive analysis of European 20th century schools of piano playing, see Fonseca, 2004.

[6] Philadelphia: Th. Pressler, 1890 (Vol. 1), 1891 (Vols. 2 and 3), 1892 (Vol. 4). A revised, more complete edition was published subsequently, in 1906.

[7] Concerning the technical demands of piano works by the mentioned composers, see Caillet, 2007, p. 55.

[8] I wish to thank Tiago Quintas for producing the transcribed musical examples in this article.

[9] My experience as a student of Yvonne Loriod’s has been recorded in a reflexive text I wrote for Catherine Lechner-Reydellet’s book Messiaen, L'empreinte d'un géant, published in 2008; cf. Lechner-Reydellet, 2008, pp. 93-103.

[10] Estas indicações dinâmicas extremas podem encontrar-se em obras do início do século XX, tais como Fête Dieu à Séville (composta em 1906), terceira peça de Iberia de Isaac Albeniz (Albeniz, 1961).

[11] Irei focar-me sobretudo em obras de eminentes pianistas da chamada Escola Pianística Russa, visto que, enquanto intérprete, me identifico particularmente com ela, tendo sido formada de acordo com os princípios dessa escola pelas pianistas Tânia Achot (na Escola Superior de Música de Lisboa, entre 1991 e 1995) e Nina Svetlanova (na Manhattan School of Music de Nova Iorque, entre 1995 e 1999). Para uma análise abrangente das escolas pianísticas europeias do século XX v. Fonseca, 2004.

[12] Philadelphia: Th. Pressler, 1890 (Vol. 1), 1891 (Vols. 2 and 3), 1892 (Vol. 4). Uma edição revista, mais completa, foi editada posteriormente, em 1906.

[13] A respeito das exigências técnicas das obras para piano dos compositores citados, v. Caillet, 2007, p. 55.

[14] Agradeço a Tiago Quintas a produção dos exemplos musicais transcritos neste artigo.

[15] A minha experiência como aluna de Yvonne Loriod ficou registada num texto de reflexão que escrevi para o livro de Catherine Lechner-Reydellet Messiaen, L'empreinte d'un géant, publicado em 2008; cf. Lechner-Reydellet, 2008, pp. 93-103.

Ana Telles

Universidade de Évora

Professora Catedrática

Portuguese pianist Ana Telles has pursued musical studies in Lisbon, New York and Paris, with Yvonne Loriod-Messiaen, Sara Buechner e Nina Svetlanova (Piano), among others. She has graduated from Escola Superior de Música de Lisboa («Bacharelato»), Manhattan School of Music (Bachelor’s Degree in Piano Performance) and New York University (Master’s Degree in Piano Performance). She holds a doctoral degree in Music History and Musicology from the Paris IV University (Sorbonne) and the University of Évora (Portugal), where her research studies were directed by Danièle Pistone and Rui Nery; her thesis on Portuguese composer Luís de Freitas Branco’s piano music was distinguished with the highest classification. Ana Telles plays regularly in Portugal, Germany, France, Italy, Spain, Ireland, Poland, the UK, South Korea, Taiwan, Cuba, Brazil and the United States, as a soloist or integrated in chamber music groups. She is Associate Professor with Habilitation at the University of Évora's Music Department and Director of the School of the Arts of the same university. A full member of CESEM Music and Musicology Research Lab, she develops research projects in the fields of Music of the 20th and 21st centuries, Portuguese modern and contemporary music, Piano music. She has authored a significant number of book chapters, papers in peer-reviewed journals and musical editions, including a critical edition of Luís de Freitas Branco’s Piano Preludes (AvA Musical Editions); her discography includes sixteen published CD’s.